Snapping stops to vehicle trajectories

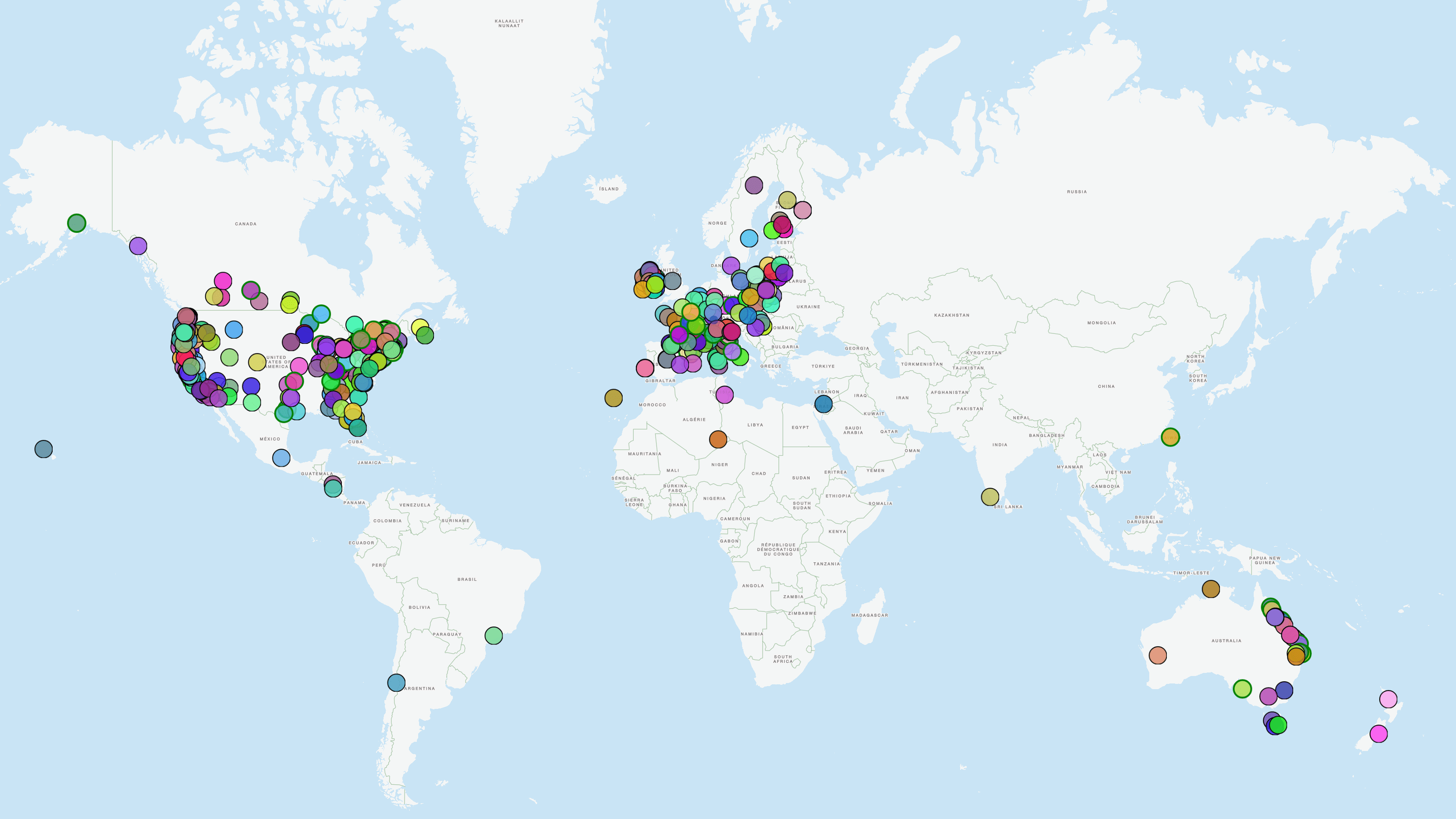

When importing timetable data including vehicle trajectories, one is often confronted with the problem of associating the calls at the stops of a trip with locations along the vehicle trajectory. The most prominent example is a GTFS feed including a shapes.txt file. The vehicle trajectory is given as one entity covering the whole trip. In addition, the spatial locations of the stops are available. The problem of splitting up the trajectory at the stops is trivial if the split locations are just the stops projected to the vehicle trajectory. But it is not always that easy. Think for example of a bus serving a stop A and then driving back on the same road and serving another stop B as illustrated in figure 1. Where should the stop be placed: On the way to A or on the way back? The answer is clear: On the way back since the order of the calls in the timetable tells us so. But from a geometric perspective alone, it is not clear at all since both branches could be the closest point on the trajectory depending on the location that is stored for the stop. Even if all the stops would be positioned exactly on the trajectory (which is typically not the case), this would not solve the problem in general since the trajectory could overlap with itself at a stop location.

The GTFS standard provides a tool to solve this problem: Each vertex of the trajectory is assigned a distance value (kilometrage). Then for each call of a trip, the exact location on the trajectory can be identified by a corresponding distance value. But experience from real data sources tells us that this kilometrage is sometimes missing, inaccurate or plain wrong. Typical errors are:

- missing or incomplete kilometrage for the trajectory

- missing or incomplete kilometrage for the call

- different yet unknown units for trajectory and call kilometrage

- inaccurate kilometrage for the calls

- nonsensical stop locations

Thus our task is twofold: Determine when to trust the given kilometrage and solve the snapping problem for the case of missing/incomplete kilometrage.

Preprocessing kilometrage data

In a first step, we check the stop locations: If they are too far away from the trajectory, we give up and ignore the corresponding trip. If the stop locations are fine, we proceed as follows for the kilometrage data: First we check the kilometrage of the trajectory. If there are at least two vertices assigned with a distance and all distances are non-decreasing and the total distance spanned is non-zero, we trust the trajectory distances. Missing distance values are complemented by linear interpolation and extrapolation using the existing values and a measurement of the true inter-vertex distances.

If this step was not successful, the kilometrage for the calls is discarded completely. Otherwise we look at each call: Let d_proj be the shortest distance of the stop to the trajectory and d_call the distance between the stop and the location on the trajectory as given by the kilometrage. Then we trust the kilometrage if d_call <= delta_rel * d_proj + delta_abs holds. The relative and absolute tolerances delta_rel and delta_abs are parameters that may depend on the mode of transport or vary if it is known that the trajectories are generalized geometries and don't follow the true infrastructure closely. Distance values failing this check are discarded.

At this point we have some (or even none) of the calls equipped with a trusted kilometrage and for the remaining calls we only know their spatial location and their order in the trip which brings us to the snapping problem.

The snapping problem

Now what exactly is the snapping problem? Given a sequence of points (the calls at the stops) and a line string (the vehicle trajectory), we are looking for a sequence of locations along the line string that minimizes the sum of square distances to the given points with the constraint that we always have to move forward along the trajectory. Or more generally speaking: We have conditions for the spacing between consecutive locations along the trajectory. For example we might require that we have to move at least 50 meters along the trajectory before stopping at the next call.

In order to be able to seamlessly deal with metric measurements, we use the EPSG:4978 coordinate system which is an earth centered, earth fixed right handed metric 3D Cartesian coordinate system based on the WGS84 ellipsoid. It has the feature that Cartesian distance measurements are very accurate: The error for a straight line segment with 100 kilometers length is only about 1 meter compared to the true geodesic length, independent from the location of the line segment on the earth surface. Typical vertex distances are way smaller than 100 km.

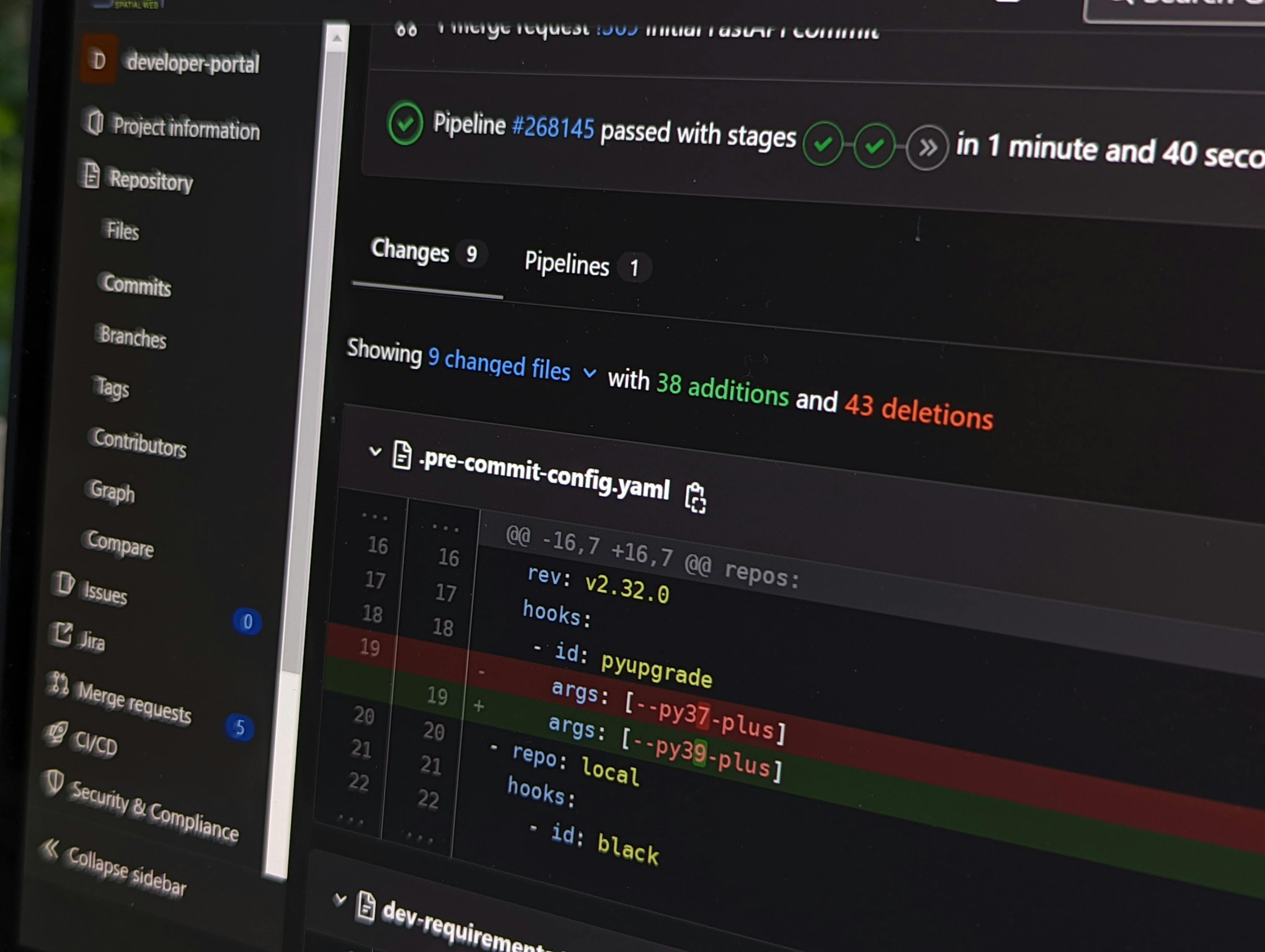

Our current approach to the snapping problem is based on an approximate, iterative algorithm that depends on initial conditions. This is however fragile, complicated and fails in tricky cases. Thus we have come up with an algorithm for the exact solution of the problem which we have published in our latest release of the PySnapping library. The idea is illustrated in figure 2: Based on the shortest distances of the stops to the trajectory, we calculate radii within the snapping can take place to still make sense. Then we intersect the corresponding balls with the trajectory and resample new vertices on the intersecting trajectory fragments. Those vertices are the candidates where the snapped stops can end up for the calls. Then we build a layered directed acyclic graph (layered DAG) where each layer corresponds to the candidates of a call. Each candidate is connected to each candidate in the next layer by an edge and we add additional sentinel nodes at the start and end. Then we set the weight of each edge to the square distance of the stop to the candidate vertex if the transition from the previous layer is admissible (minimum spacing/order intact). If the transition violates the minimum spacing/order, we set the weight to infinity. The weights of the terminal edges at the end node are zero.

If a finite solution exists, it is then given by the finite shortest path through the DAG from the sentinel start to end node since the shortest path length is per definition of our edge costs the sum of square distances. The constraints of the minimum spacing conditions hold since we only used admissible transitions. The calls with trusted kilometrage can easily be incorporated by picking exactly one candidate vertex corresponding to the known location on the trajectory in the particular layer of the DAG.

Time Complexity

We conclude with a few words about the time complexity of the algorithm. The shortest path problem can be solved very elegantly for this special type of graph by only constructing edges that really have to be explored on the fly. For each candidate in a given layer, we only have to consider the shortest paths to reachable candidates in the previous layer and then find the minimum cost by adding one more edge. But the cost for this additional edge is either infinite or constant! Thus we have to find the minimum over all candidates in the previous layer which have an admissible extension to the current layer. If we sort the candidates by their location along the trajectory, this problem reduces to calculating the cumulative minima once per layer and finding out which edges are admissible. We can use a bisection search with increasing lower bound to find the range of admissible edges for each candidate. Let N_cand be the number of candidate vertices per layer. Calculating the cumulative minima is O(N_cand) per layer and the bisection search is O(N_cand * log(N_cand)) per layer.

Since we are only interested in meaningful solutions, we have restricted the search to balls with certain radii. If we assume that trajectories tend to move around and don't stay located for too long in a certain area, we thus can conclude that the number of candidate nodes in each layer of the graph is basically constant and does not depend on the length of the trajectory or the number of calls. This assumption is reasonable for vehicle trajectories in public transport since the intent of public transport is to bring people from A to B without unnecessary detours. The shortest path can thus be found in linear time in the number of calls with a low constant. For the intersection of the balls with the line string, we currently check all vertices which is linear in the number of calls times the number of vertices of the line string. This could possibly be sped up by using a spatial index for long line strings.

Our implementation is currently in pure Python and NumPy. Before replacing our current iterative algorithm, we plan to profile the new algorithm on typical data sources and depending on the outcome, we might use Cython for isolated parts of the algorithm or take into account using a spatial index for long trajectories.